Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | iHeartRadio | TuneIn | RSS | More

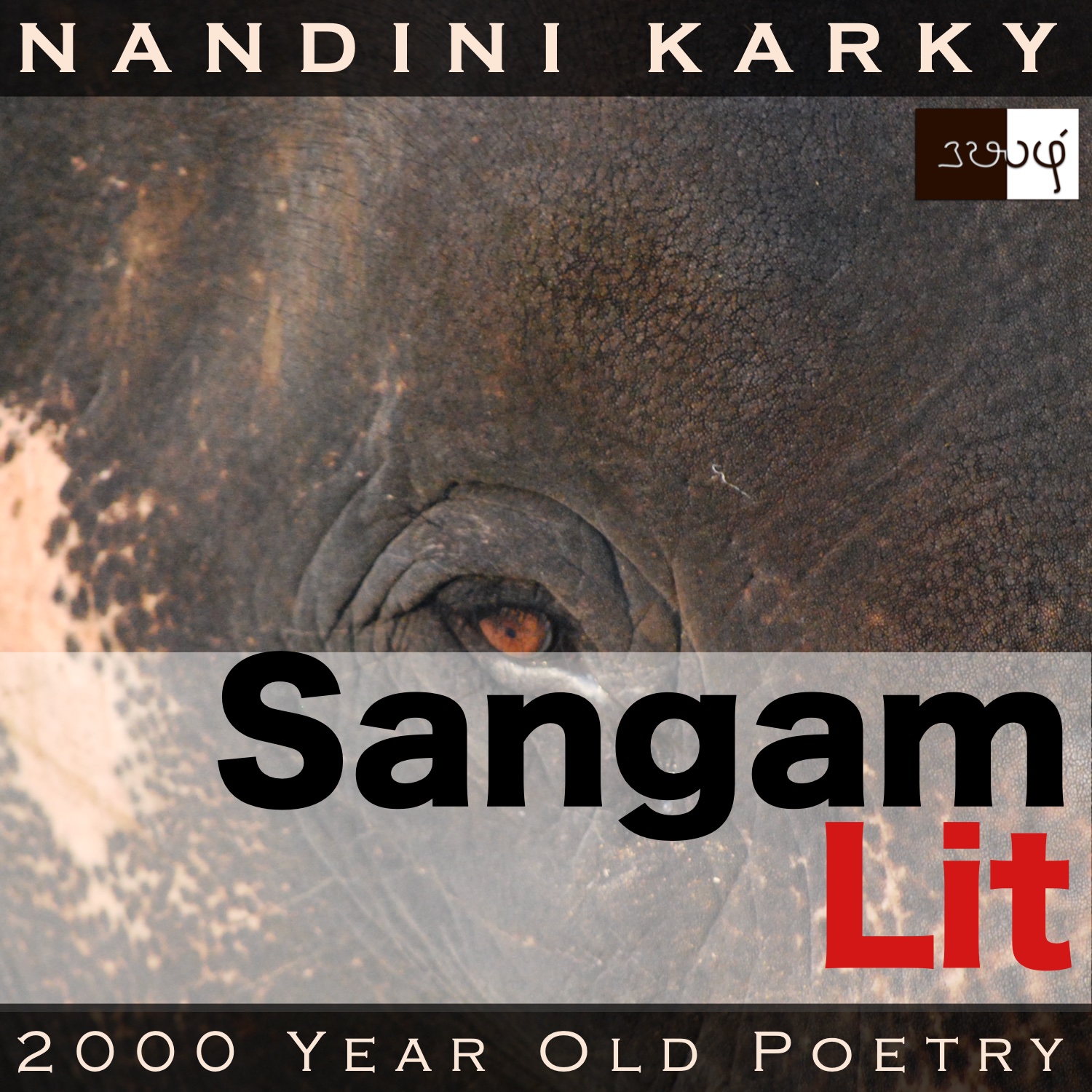

In this episode, we perceive the poignant feelings in a man, as portrayed in Sangam Literary work, Kurunthogai 142, penned by Kabilar. The verse is situated in the hills of ‘Kurinji’ and speaks in the voice of the man to his heart, expressing his angst in parting with his lady after their union.

சுனைப்பூக் குற்றுத் தொடலை தைஇ,

புனக் கிளி கடியும் பூங் கட் பேதை

தான் அறிந்தன்றோ இலளே-பானாள்

பள்ளி யானையின் உயிர்த்து, என்

உள்ளம், பின்னும், தன் உழையதுவே!

A verse that makes us sense the sighs in separation. The opening words ‘சுனைப்பூக் குற்றுத் தொடலை தைஇ’ link two nouns and two verbs for they mean ‘plucking mountain spring flowers and weaving garlands’. ‘பூங் கட் பேதை’ talks about ‘an innocent maiden with flower-like eyes’. In the phrase ‘பானாள் பள்ளி யானையின் உயிர்த்து’ meaning ‘sighing like a sleeping elephant at midnight’, we hear the loud breathing of a sleeping giant. Curious how the word ‘உயிர்த்து’ which means ‘alive’ is associated with ‘breathing’ – Seems to me like a Tamil single-word portrait of the English expression ‘breath of life’. Ending with the words ‘தன் உழையதுவே’ meaning ‘languishes on its own’, the verse invites our empathy.

Flower-eyed maidens have no doubt something to do with the languishing! The context reveals that the man had met the lady and fallen in love with her. She too reciprocates his feelings and they both unite. After a while, the man parts away. At this time, he turns to his heart and says, “She makes garlands with flowers plucked from the springs and chases away parrots in the millet field – Does that flower-eyed, naive maiden know this or not? That, sighing like a sleeping elephant at midnight, my heart, after I part from her, stays back languishing.” With these words, the man declares the pain in parting with his lady after their union and his deep wish of being close to her.

Time to visit the nuances in the verse. The man starts by narrating all the things he imagines the lady would be doing just then. He sees her visiting those lush springs in the mountains and picking blue lotuses, lilies and other flowers that abound there. Having plucked these flowers, the lady weaves garlands with the same, creating delightful objects of beauty. Apart from these artistic pursuits, she seems to be taking part in the practical needs of her family by chasing parrots that come to raid their millet fields. Sounds like a busy young girl, who the man then describes as a maiden with eyes like those very flowers she plucks. And he wonders if she even realises what’s happening to him. What might that be?

Focusing on an elephant that is sleeping in the dark hours of midnight, the man beckons us closer and we can hear its loud breathing. Just then, the man turns to us and tells us that’s exactly how his heart seems to be sighing in pain, on having parted from the lady. Two things stand out in this verse to me! One is that capture of a sleeping elephant. Today, we have stunning nature documentaries that make us experience wild life in exquisite detail, courtesy Sir David Attenborough. But, two thousand years ago, without the aid of modern technology, such vivid captures have relied purely on human observation. Did these Sangam poets spend a considerable portion of their education deeply studying plants and animals, to carve such detailed portraits of nature? Leaving those unanswerable questions now, let us move on to the other striking aspect in this verse and that is how the feelings of angst in a man are normalised, much against our modern conditioning, which seems to relegate these difficult emotions to women and pretend as if men are immune to the same. When it comes to love and emotions, gender matters not, this ancient poet seems to say. If we lean in to listen, we can hear the whisper of a wise voice from the past saying, ‘feel free to feel whatever you feel’.

Share your thoughts...