Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | iHeartRadio | TuneIn | RSS | More

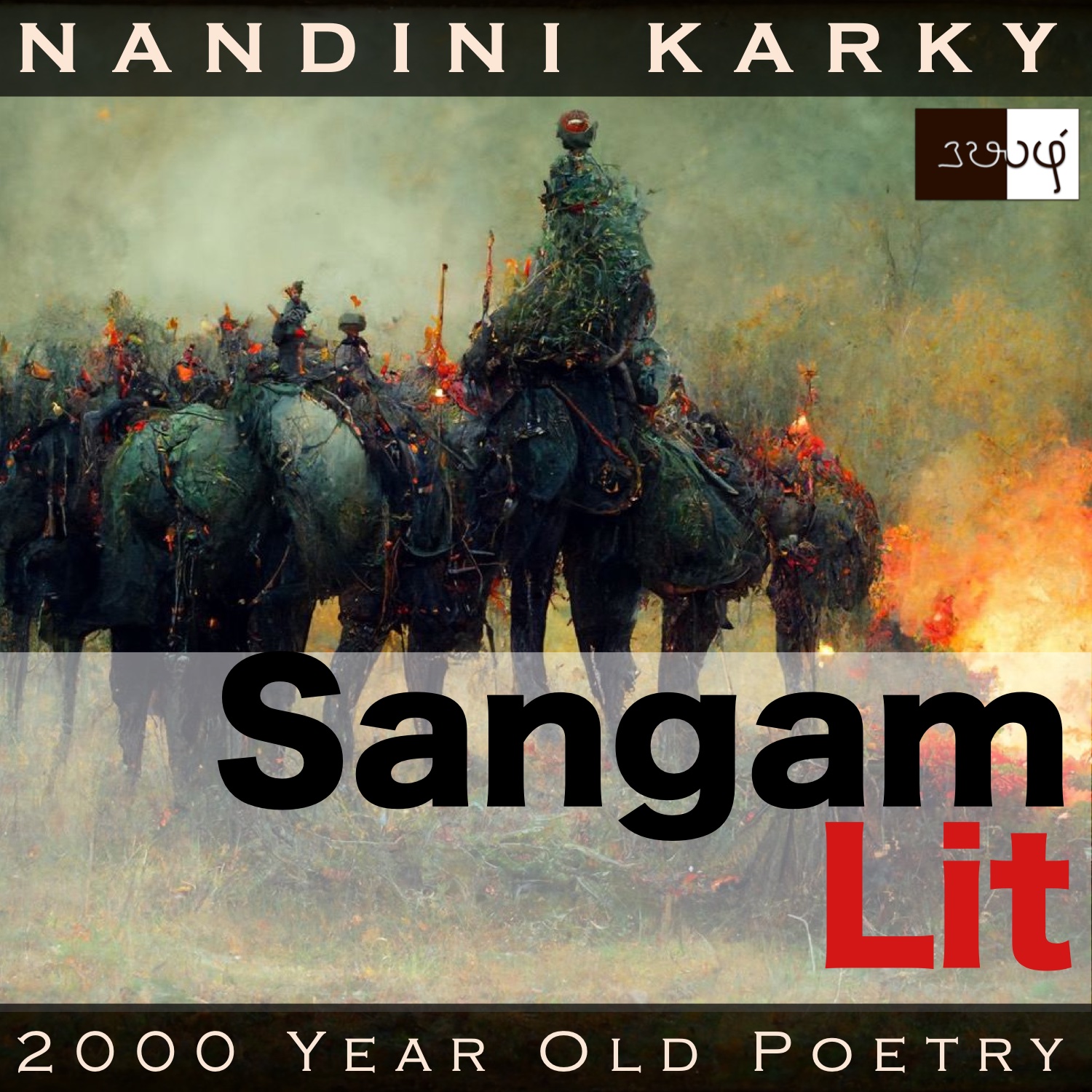

In this episode, we perceive a king’s actions in a war, as portrayed in Sangam Literary work, Puranaanooru 16, penned about the Chozha King Raasasooyam Vetta Perunarkilli by the poet Paandarankannanaar. Set in the category of ‘Vanji Thinai’ or ‘a king’s prowess in the battlefield’, the verse talks about the ruin brought about on enemy lands.

வினை மாட்சிய விரை புரவியொடு,

மழை உருவின தோல் பரப்பி,

முனை முருங்கத் தலைச் சென்று, அவர்

விளை வயல் கவர்பூட்டி,

மனை மரம் விறகு ஆகக்

கடி துறை நீர்க் களிறு படீஇ,

எல்லுப் பட இட்ட சுடு தீ விளக்கம்

செல் சுடர் ஞாயிற்றுச் செக்கரின் தோன்ற,

புலம் கெட இறுக்கும் வரம்பு இல் தானை,

துணை வேண்டாச் செரு வென்றி,

புலவு வாள், புலர் சாந்தின்,

முருகற் சீற்றத்து, உரு கெழு குருசில்!

மயங்கு வள்ளை, மலர் ஆம்பல்,

பனிப் பகன்றை, கனிப் பாகல்,

கரும்பு அல்லது காடு அறியாப்

பெருந் தண் பணை பாழ் ஆக,

ஏம நல் நாடு ஒள் எரி ஊட்டினை,

நாம நல் அமர் செய்ய,

ஓராங்கு மலைந்தன, பெரும! நின் களிறே.

This song purely focuses on what a king does in the battlefield, not as a portrait of him, as we have seen in the songs of ‘Paadan Thinai’ thus far, but as an elaboration of his actions. The poet’s words describing this Chozha king in the battlefield can be translated as follows:

“On speedy horses, skilled in their work, spreading a leather saddle in the hue of clouds, making enemy lines shiver, racing forward towards their fertile lands, you plunder them.

You send elephants to well guarded water tanks. Then, turning wood of houses into firewood, you set fire, the glowing light of which appears in the crimson hues of the setting sun.

Without a spot of space to be in, limitless spreads your army, and so, you win battles without any need for the aid of allies. With a flesh-smelling sword, dried sandalwood paste, and the fury of Lord Murugu, appears your magnificent form, O king!

The lush and moist farmlands that know not what forests are but know only field bindweed, blooming pink waterlily, winter’s blue rattlepod, bitter melon fruit and sugarcane. Ruining all this, you set ablaze the well-protected, fine country. To perform the task of waging war efficiently, as one, they all fight together, those elephants of yours, O lord!”

Let’s delve into the intricacies of this ancient action segment! The poet starts by sketching a scene where soldiers are rushing on fast horses, mounted on saddles that look like clouds, as they speed towards the lush fields in the enemy nation, with the intention of destroying them. Enemy’s food supply now being targeted. Next in line, should be water, and as expected, battle elephants are sent to make the well-guarded pond waters murky and polluted. Adding that the king’s army was so huge in number that seemed limitless to the eyes, the poet narrates how the troops of allies having no place to be, returned back. A unique way of saying that although many were ready to extend their support, the king needed help from no one to win his battles. At this moment, the poet presents a brief portrait of the king, sketching how he can be seen with a flesh-reeking sword in hand, with the sandalwood on his chest dried in his exploits and appearing with the rage of God Murugu himself!

Using the very wood of the houses in the enemy country, the king’s army then sets fire and the reddish light of that blaze reminds one of the twilight sky when the sun bids bye. The poet then reveals what they are setting fire to, by pointing in the direction of lush agricultural lands, which he describes as not knowing forests. That is an intricate observation which tells us that this land has long ago been turned into a farmland, and has been, for generations, under the plough. This is not some freshly cleared forest track, where agriculture is just being begun but a well-established farmland, an indicator of the prosperity of the king who owns the same. To make the point even clearer, the poet talks about how these field lands know not of the wild but only tame plants like the bindweed, waterlily, rattle pods, melon fruits and most importantly, the prime crop of sugarcane. But what’s the use? No matter how prosperous a yield those fields give, now they lay a prey to the king’s torches, reduced to ashes. The poet concludes with the words that to fulfil all these intentions of the king at war, his army of elephants worked together as one!

Fire, red, ruin, flesh and blood – These are the elements that this poem evokes in us! As in the case of ‘Aham’ poems, when we wondered why song after song speaks of the pining of a woman in love, now the question arises in ‘Puram’ poetry, as to why in song after song, battles and bloodshed are being described. Is it only in praise of the king’s prowess in the battlefield or could it be a subtle way of revealing the dire consequences of the king’s actions in the enemy land, in the hope of reducing its magnitude the next time over? We have no answers for these questions on intent but we do have this content of history nudging us to question the need for wars and bloodshed!

Share your thoughts...