Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | iHeartRadio | TuneIn | RSS | More

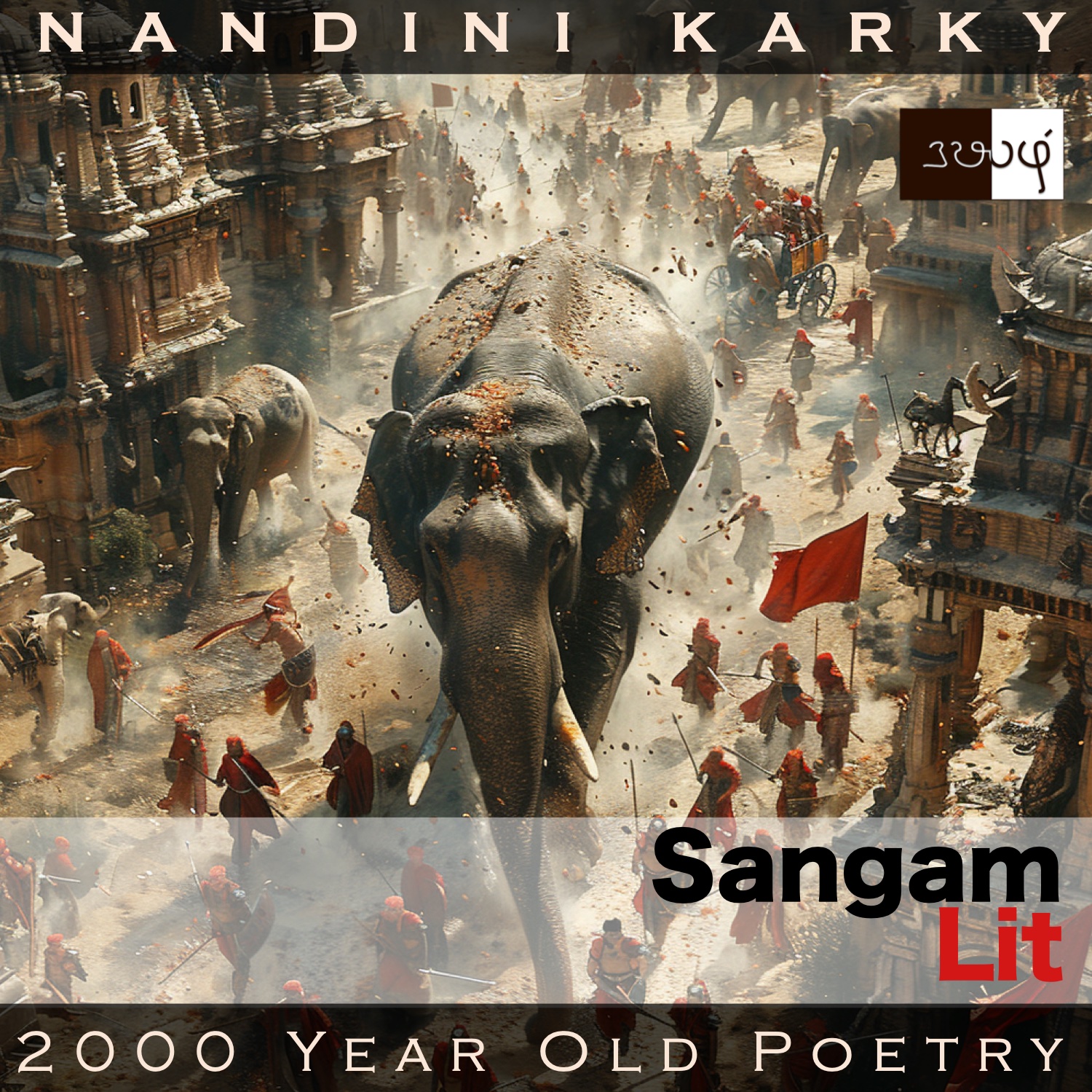

In this episode, we observe a perfect instance of projection, as depicted in Sangam Literary work, Puranaanooru 369, penned for the Chera King Kadalottiya Velkelu Kuttuvan by the poet Paranar. Set in the category of ‘Vaagai Thinai’ or ‘Victory’, the verse puts forth a specific request to a winning king in the battlefield.

இருப்பு முகஞ் செறித்த ஏந்து எழில் மருப்பின்,

கருங் கை யானை கொண்மூ ஆக,

நீள்மொழி மறவர் எறிவனர் உயர்த்த

வாள் மின் ஆக, வயங்கு கடிப்பு அமைந்த

குருதிப் பலிய முரசு முழக்கு ஆக,

அரசு அராப் பனிக்கும் அணங்கு உறு பொழுதின்,

வெவ் விசைப் புரவி வீசு வளி ஆக,

விசைப்புறு வல் வில் வீங்கு நாண் உகைத்த

கணைத் துளி பொழிந்த கண் அகன் கிடக்கை

ஈரச் செறுவயின் தேர் ஏர் ஆக,

விடியல் புக்கு, நெடிய நீட்டி, நின்

செருப் படை மிளிர்ந்த திருத்துறு பைஞ் சால்,

பிடித்து எறி வெள் வேல் கணையமொடு வித்தி,

விழுத் தலை சாய்த்த வெருவரு பைங் கூழ்,

பேய்மகள் பற்றிய பிணம் பிறங்கு பல் போர்பு,

கண நரியோடு கழுது களம் படுப்ப,

பூதம் காப்ப, பொலிகளம் தழீஇ,

பாடுநர்க்கு இருந்த பீடுடையாள!

தேய்வை வெண் காழ் புரையும் விசி பிணி

வேய்வை காணா விருந்தின் போர்வை

அரிக் குரல் தடாரி உருப்ப ஒற்றி,

பாடி வந்திசின்; பெரும! பாடு ஆன்று

எழிலி தோயும் இமிழ் இசை அருவி,

பொன்னுடை நெடுங் கோட்டு இமையத்து அன்ன

ஓடை நுதல, ஒல்குதல் அறியா,

துடி அடிக் குழவிய பிடி இடை மிடைந்த

வேழ முகவை நல்குமதி

தாழா ஈகைத் தகை வெய்யோயே!

As we saw in the previous verse, this scene in a battlefield is presented in a different light. The poet’s words can be translated as follows:

“With beautiful, uplifted tusks adorned with iron tipped ornaments, elephants with black trunks become clouds; Swords raised by soldiers, who have taken tall vows become lightning; War drum to which sacrificial offerings have been rendered and that which is struck by short sticks becomes thunder; Enemy kings become snakes filled with fear in that frightening time; Speeding horses become the roaring wind; Arrows that are emitted by the swelling and taut strings of the bow become rain drops in that wide-spreading space; In that moist field, chariots become the ploughs; Arriving at dawn, extending tall, your many weapons shine and pounce upside down, and along with thrown white spears, become the seeds, and finally, heads and bodies torn asunder become the fresh crop of corpses that are stacked high as haystacks around which ghostly maiden, flocks of foxes and fearsome ghosts rove around, as ghouls stand in guard in that rich crop field, O great king who awaits the bards!

Smeared with the paste of white sandalwood freshly ground on a stone, with a flawless new cover, is my resounding thadari drum that I come beating and singing to you, O lord! Akin to the tall and golden peaks of the Himalayas, with resounding cascades watered by the roaring clouds, wearing ornaments, knowing not what it’s to be tame, a male elephant along with its female and small-trunked calves, you must render unto me, O great king, who desires the fame that springs from unceasing generosity!”

Let’s delve into the nuances. This prolific historian-poet sketches an ancient battlefield for us, but not in a direct style. Rather, he transposes this battlefield to an entirely different occupational area. To explain, the poet says the elephants in that battlefield are not just elephants but are dark clouds in the sky. Next, the swords held by soldiers are lightning rods, he says, following this by equating the resounding war drums to thunder heard in the sky. Signs of rain in the sky of this verse! In tandem with the belief of these Sangam people that thunder ruins snakes, as we have seen in many songs in both Aham and Puram categories of Sangam literature, this crucial element of snakes in the rain is defined as none other than enemy kings, who are frightened by the outburst of those dark clouds of elephants, lightning streaks of swords and thundering war drums. Next, leaping horses turn into the wind that blows with fierceness and arrows are said to be the rain drops that fall on the battlefield. So far, it’s all elements of weather that’s been equated to elements of war, but now the poet turns it into occupational elements by equating chariots to the ploughs on a field as well as connecting spears and other weapons that pounce upside down to seeds. From this, arises the crop of heads and bodies torn apart, and the harvest of corpses that are claimed by roving ghost maiden, foxes and ghouls many, the poet completes. Though these images of battlefield are gruesome and not to our liking, we have to appreciate the skills of connection in this poet who sees something, and then in that, is able to perceive an entirely different thing. In this field of death, the poet is able to visualise a field of life-giving crops and that is indeed creativity par excellence!

After that visual table of comparison, the poet turns to his own situation and mentions how he has brought a drum covered in fresh sandalwood paste, that he plays on and sings to this king, hoping for a gift from that conqueror. It’s not any old thing that this chap wants but specifically a male elephant, towering like a Himalayan peak, and its entire family of female elephants and calves as well. He concludes as if he’s asking this only to fulfil the king’s desire for earning fame through such splendid generosity.

It was a different world and perhaps those poets could demand and expect to receive such exorbitant gifts from patrons. These days, poets need a second job even to survive! It makes sense that poets were so highly valued in that era because their output was that the equivalent of modern theatre, TV and cinema, all rolled into one. Reverting back to that image of the crop field, the way the poet opens not with agricultural elements but with rain, thunder and lightning underscores the inextricable dependancy between farming and weather, something that’s a subtle positive element of knowledge that we can mine from this otherwise gruesome minefield of death!

Share your thoughts...