Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | iHeartRadio | TuneIn | RSS | More

In this episode, we hear the impactful words of the lady’s confidante, as depicted in Sangam Literary work, Ainkurunooru 51 to 60, situated in the ‘Marutham’ or ‘Farmlands landscape’ and penned by the poet Orambokiyar.

Thus flows the Sixth Ten of Ainkurunooru : Heed to the Confidante

51 Craving of the heart

நீர் உறை கோழி நீலச் சேவல்

கூர் உகிர்ப் பேடை வயாஅம் ஊர!

புளிங்காய் வேட்கைத்து அன்று, நின்

மலர்ந்த மார்பு இவள் வயாஅ நோய்க்கே.

O lord of the town, where the sharp-clawed female water fowl seeks its blue-hued mate with a deep craving! Your wide chest is akin to the yearning to eat tamarind, for her disease of desire!

52 Chariot streaking red

வயலைச் செங் கொடிப் பிணையல் தைஇச்

செவ் விரல் சிவந்த சேயரி மழைக் கண்

செவ் வாய்க் குறுமகள் இனைய;

எவ் வாய் முன்னின்று மகிழ்ந! நின் தேரே?

After she wove a garland with the red vines of the ‘vayalai’, the red fingers reddened further in this young maiden with line-streaked, red eyes and a red mouth. Making her feel sad, in front of whose gate did your chariot stand?

53 Pouncing wild stream

துறை எவன் அணங்கும், யாம் உற்ற நோயே?

சிறை அழி புதுப் புனல் பாய்ந்தெனக் கலங்கிக்

கழனித் தாமரை மலரும்

பழன ஊர! நீ உற்ற சூளே.

How would the god residing in the shore affect her disease? This is about oath you took, O lord, in whose pond-filled town, new, wild streams, breaking barriers, flood and muddle the fields, where lotuses bloom.

54 His fear-evoking women

திண் தேர்த் தென்னவன் நல் நாட்டு உள்ளதை

வேனில் ஆயினும் தண் புனல் ஒழுகும்

தேனூர் அன்ன இவள் தெரிவளை நெகிழ,

ஊரின் ஊரனை நீ தர, வந்த

பைஞ்சாய்க் கோதை மகளிர்க்கு

அஞ்சுவல், அம்ம! அம் முறை வரினே.

In the country of the southern king, who wields sturdy chariots, even if it’s summer, cool streams gush in the town of ‘Thenoor’. Akin to that is she! Making her well-etched bangles slip away, you went away to another town within the town. Listen! Thinking about the time when I have to come call you to do your duties, I fear for those women, wearing garlands of sedge!

55 Pallor-filled forehead

கரும்பின் எந்திரம் களிற்று எதிர் பிளிற்றும்,

தேர் வண் கோமான், தேனூர் அன்ன இவள்

நல் அணி நயந்து நீ துறத்தலின்,

பல்லோர் அறியப் பசந்தன்று, நுதலே.

The sugarcane machine trumpets like a male elephant in your town, O lord with beautiful chariots! Because you abandoned the fine beauty of she, who is akin to Thenoor, making it evident to many, her forehead spread with pallor!

56 Useless words

பகல் கொள் விளக்கோடு இரா நாள் அறியா,

வெல் போர்ச் சோழர், ஆமூர் அன்ன இவள்

நலம்பெறு சுடர் நுதல் தேம்ப,

எவன் பயம் செய்யும், நீ தேற்றிய மொழியே?

With lamps that shower light, as if it was day, not knowing what is the darkness of the night, glows the town of Amoor, in the domain of the conquering Cholas! Akin to this town, is she, and making the beautiful, radiant forehead of hers lament, you left. What use is it of now, those words of appeasement you render?

57 Can her beauty compare?

பகலில் தோன்றும் பல் கதிர்த் தீயின்

ஆம்பல் அம் செறுவின் தேனூர் அன்ன

இவள் நலம் புலம்பப் பிரிய,

அனைநலம் உடையோளோ மகிழ்ந! நின் பெண்டே?

Akin to the many-rayed fire that appears in the day, is the town of ‘Thenoor’, filled with picturesque fields where white waterlilies bloom. Akin to this town, is she, and making her good beauty fade, you went away. Does she have so much beauty, O lord of the town, that mistress of yours?

58 The same to all women

விண்டு அன்ன வெண்ணெல் போர்வின்,

கை வண் விராஅன், இருப்பை அன்ன

இவள் அணங்குற்றனை போறி;

பிறர்க்கும் அனையையால்; வாழி நீயே!

Akin to soaring peaks, appear the mounds of white rice in the town of ‘Iruppai’, ruled by the generous ‘Viraan’. Akin to this town is she, and before her, you seem to be afflicted with regret. However, you act the same before other women too. May you live long!

59 No more the cure

கேட்டிசின் வாழியோ, மகிழ்ந! ஆற்றுற,

மையல் நெஞ்சிற்கு எவ்வம் தீர

நினக்கு மருந்து ஆகிய யான், இனி,

இவட்கு மருந்து அன்மை நோம், என் நெஞ்சே.

Listen to what I have to say! May you live long, O lord of the town! To console her, and end the suffering of her desire-filled heart, I became the cure for you then. But now, this heart of mine laments that I’m unable to be the cure any more.

60 The call of the female

பழனக் கம்புள் பயிர்ப்பெடை அகவும்

கழனி ஊர! நின் மொழிவல்: என்றும்

துஞ்சு மனை நெடு நகர் வருதி;

அஞ்சாயோ, இவள் தந்தை கை வேலே?

O lord with towns, filled with fields, where the loving female of the common coot calls aloud in the marshy ponds! I say to you, you seem to come to the sleeping mansion all the time. Don’t you fear the spear held in the hand of her father?

Thus concludes Ainkurunooru 51 to 60. All these songs except the last one is set in the context of the man’s parting after marriage, seeking other women. The last song is one set before the lady’s marriage with the man, in a time when they were having a secret relationship. The unifying element of all these ten verses is that it’s the lady’s confidante, who renders these words, and in all cases, it is said to the man.

In our usual manner, let’s look at the direct second part of the verse. In the first, the confidante refuses entry to the man, placing the man’s chest as parallel to the craving in the lady to eat tamarind. Even when the confidante tries to stop her, the lady keeps accepting the man, and he too, after returning, soon abandons the lady to go to his courtesans. Although the man is fickle, the lady still seeks him with desire like that craving for tamarind, the confidante declares, extolling her virtues and scolding the man indirectly. In the second, the confidante thinks back to the time when the man went away, and queries asking, making the lady suffer, in front of whose gates, did he park his chariot? In this verse, the confidante highlights the colour red as she talks about how the lady’s fingers become redder as she plucks the red purslane vines to weave a garland, and then how, her eyes redden in that pain, and even mentions her red mouth. Perhaps this is to highlight the youth and naive nature of the lady, indirectly asking the man how could he leave her and go away.

The third verse happens in the context of the man saying to the confidante that when he and the lady were bathing in the stream, he felt that the water spirit descended on the lady for she seemed to be suffering there. Here, the confidante dispels such superstitious notions, saying no water spirit attacked the lady. She was simply thinking about whether the man had bathed in the same place with the courtesans and gave them too, an oath of never parting. No one knows the lady’s mind like her friend!

In the next five songs, in that exquisite Sangam tradition, the lady’s beauty is compared either to the Pandya town of ‘Thenoor’, where the rivers never shrink even in summer, or to the Chola town of ‘Amoor’, where the lamps that glow like the day wipe away any knowledge of darkness, or to the town of ‘Iruppai’ ruled by a Velir King Viraan, where such is the prosperity that mounds of rice are like mountain peaks. After placing the lady’s beauty in parallel to these illustrious towns, the confidante declares in the fourth, that her only fear is for how the man’s courtesans will surround him and not let him come home, when it’s time for him to go there and do his duties to his wife, when she has just delivered his child. In the successive ones, the confidante talks about pallor spreading on the lady, then declares the man’s words of appeasement are of no use whatsoever, followed by a piercing question whether the courtesan was so beautiful that made the man forsake the lady with so much beauty, and also says, the man seems to show so much regret before the lady but they are not fooled because he’s the same to other women too.

In the ninth, the confidante thinks back to how she was the cure for all the trouble the man gave when he parted away from the lady before marriage. She was able to speak words of consolation, but now, after marriage, when the man causes pain with another kind of parting, she says she’s no more able to help the lady. Finally, in the last verse, there’s a theme not usually seen in the ‘Marutham’ landscape but rather belongs to the secret relationship of the ‘Kurinji’ land, and here, the confidante asks the man whether he has no fear for the spear in the hand of the lady’s father as he comes to see the lady without fail every night to her mansion? Through this, she is nudging the man to marry the lady.

Turning our attention to the metaphorical elements, in the first by talking about cravings of the blue waterfowl, the confidante is placing a metaphor for the lady’s pregnant state, chiding the man for leaving her. In the one where she talks of the sugarcane machine roaring like an elephant, she places a metaphor for how the lady’s worry and her disappointment with the man is being relayed loudly to the town entire by the pallor that spreads on her forehead.

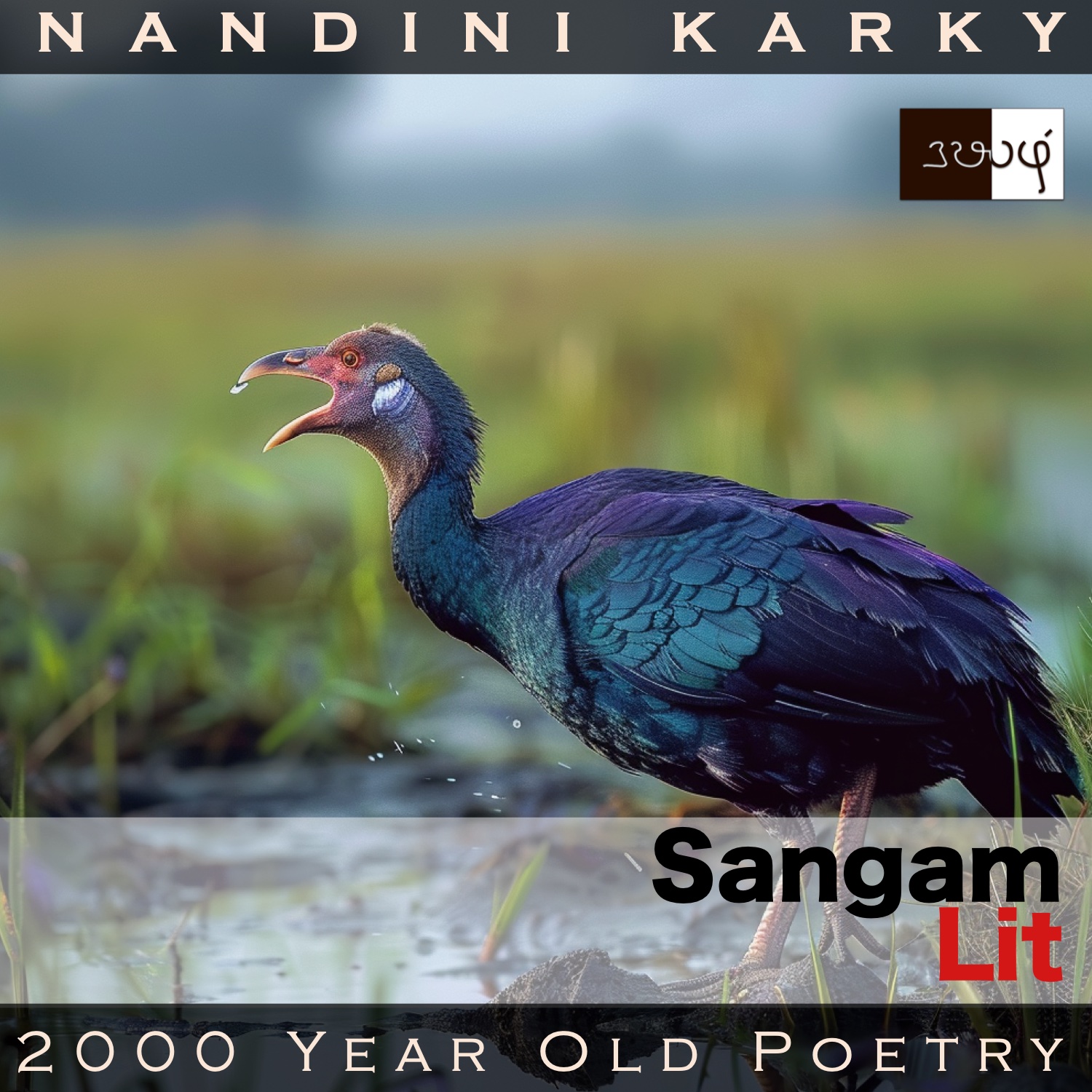

Beyond the usual laments on behalf of the lady, owing to the atrocities of the man, the highlights of this verse are the portraits of rich towns in the Sangam era, and the way these poets connect it with the beauty of a lady. What a simile! Would we dare to say with such a matter-of-fact tone, ‘a lady as charming as Chennai, or pretty as Paris’, given the many shades of these cities in the twenty-first century? But truly those towns seem to have gained the Sangam poets’ mark of approval! The other interesting facet is the depiction of a blue waterfowl, which on searching, I found out to be the vibrant-hued ‘Purple swamphen’! The Sangam poets care not only for the colourful but even the common coot’s love for its mate is captured by them. The final highlight is the depiction of the lady’s state of pregnancy and the duties that fell upon the man in these times. Fascinating to steal these glimpses of natural and social life, two thousand years ago, in these verses of few words!