Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | iHeartRadio | TuneIn | RSS | More

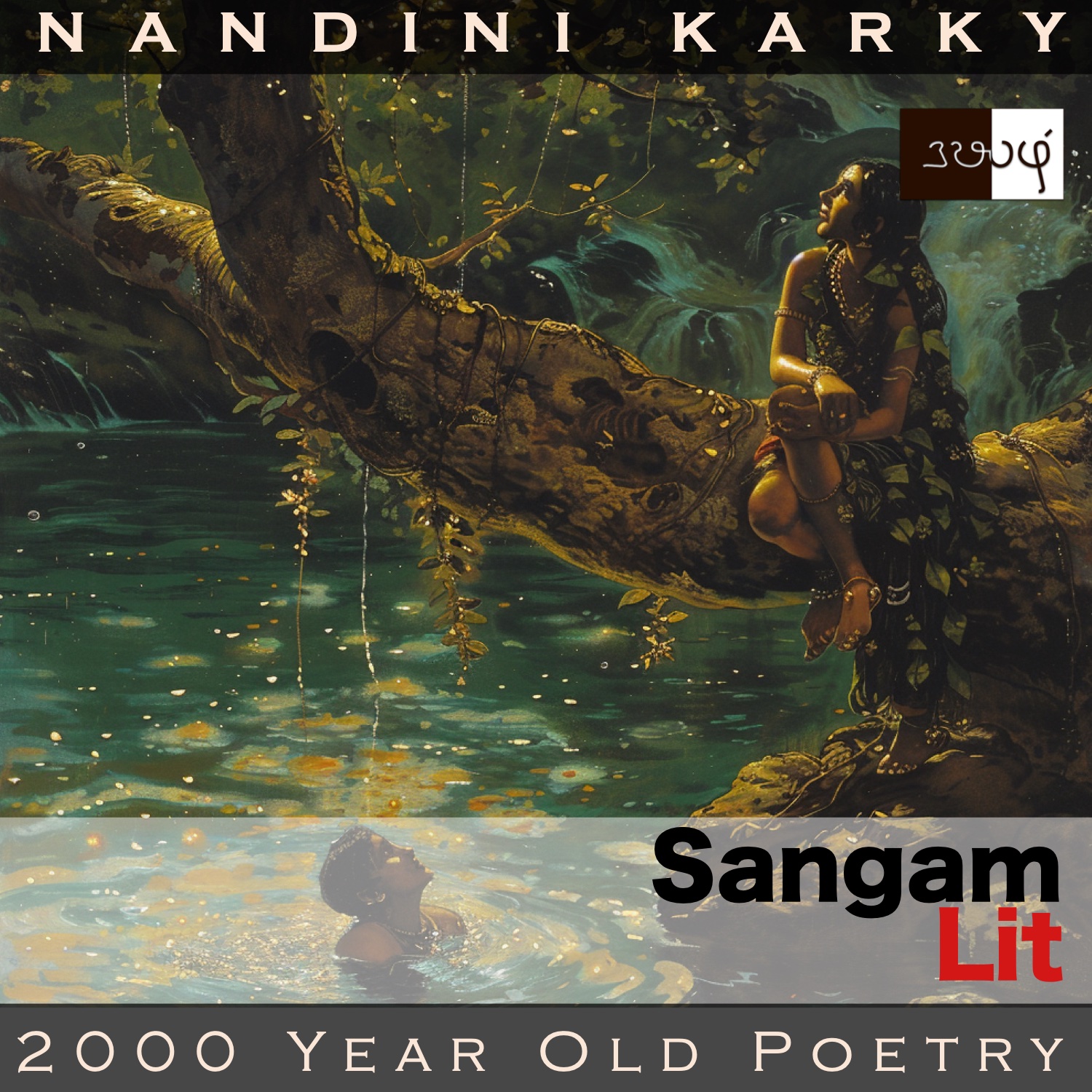

In this episode, we take a deep dive into the bathing culture of the ancients, as depicted in Sangam Literary work, Ainkurunooru 71 to 80, situated in the ‘Marutham’ or ‘Farmlands landscape’ and penned by the poet Orambokiyar.

Thus flows the Eighth Ten of Ainkurunooru: Tales of Bath

71 Glowing Gossip

சூது ஆர் குறுந் தொடிச் சூர் அமை நுடக்கத்து

நின் வெங் காதலி தழீஇ, நெருநை

ஆடினை என்ப, புனலே; அலரே

மறைத்தல் ஒல்லுமோ, மகிழ்ந?

புதைத்தல் ஒல்லுமோ ஞாயிற்றது ஒளியே?

Embracing your desirable lover, who wears small bangles with clasps, shaped like dice, and who has a seductive gait, you played in the stream yesterday, they say. Can one make rumour retreat? Can one bury the brightness of the sun?

72 My beautiful bathing mate

வயல் மலர் ஆம்பல் கயில் அமை நுடங்கு தழைத்

திதலை அல்குல், துயல்வரும் கூந்தல்,

குவளை உண்கண், ஏஎர் மெல்லியல்

மலர் ஆர் மலிர்நிறை வந்தென,

புனல் ஆடு புணர்துணை ஆயினள், எமக்கே.

With leaves of the white waterlily, blooming in the fields, well-clasped, and gliding around her waist, filled with pallor spots, swaying tresses, kohl-streaked eyes like blue lilies, was that gorgeous and delicate maiden. When the flower-filled, flooding waters gushed, she became my bathing companion then!

73 The one who makes the river fragrant

வண்ண ஒண் தழை நுடங்க, வால் இழை

ஒண்ணுதல் அரிவை பண்ணை பாய்ந்தென,

கள் நறுங் குவளை நாறித்

தண்ணென்றிசினே பெருந் துறைப் புனலே.

With colourful and glowing leaves swaying, wearing shining ornaments, having a radiant forehead, was that young maiden. When she dived into the waters, becoming fragrant with the nectar-filled scent of blue-lilies, the stream by the huge shore became cool and delightful.

74 Peacock Plume in the Sky

விசும்பு இழி தோகைச் சீர் போன்றிசினே

பசும் பொன் அவிர் இழை பைய நிழற்ற,

கரை சேர் மருதம் ஏறிப்

பண்ணை பாய்வோள் தண் நறுங் கதுப்பே.

When she gently removed her glowing gold ornaments, climbed on the ‘Marutham’ tree by the shore and dived into the waters, her cool and fragrant tresses seemed like peacock feathers descending from the sky.

75 Spreading Rumour

பலர் இவண் ஒவ்வாய், மகிழ்ந! அதனால்,

அலர் தொடங்கின்றால் ஊரே மலர

தொல் நிலை மருதத்துப் பெருந் துறை,

நின்னோடு ஆடினள், தண் புனல் அதுவே.

You have become disagreeable to many here, O lord! For rumours have started spreading in town about how by the river shore, where an age-old ‘Marutham’ tree stands, she played in the cool stream with you.

76 Water beauty

பைஞ்சாய்க் கூந்தல், பசு மலர்ச் சுணங்கின்

தண் புனலாடி, தன் நலம் மேம்பட்டனள்

ஒண் தொடி மடவரல், நின்னோடு,

அந்தர மகளிர்க்குத் தெய்வமும் போன்றே.

The woman, wearing shining bangles, having tresses, akin to soft sedge, and pallor spots, akin to fresh flowers, after bathing with you in the stream, saw her beauty soar, making her appear like a god to heavenly maiden.

77 Go not

அம்ம வாழியோ, மகிழ்ந! நின் மொழிவல்:

பேர் ஊர் அலர் எழ, நீர் அலைக் கலங்கி,

நின்னொடு தண் புனல் ஆடுதும்;

எம்மொடு சென்மோ; செல்லல், நின் மனையே.

Listen, may you live long, O lord of the town! I ask of you. Making rumours spread in our huge town, muddling these waters, I will bathe in the cool stream with you. Come with me; But don’t you go to your home.

78 Elephantine flood

கதிர் இலை நெடு வேல் கடு மான் கிள்ளி

மதில் கொல் யானையின், கதழ்பு நெறி வந்த,

சிறை அழி புதுப்புனல் ஆடுகம்;

எம்மொடு கொண்மோ, எம் தோள் புரை புணையே.

Akin to the elephants of King Killi, who wields glowing, leaf-edged tall spears and speedy horses, which shatters fort walls, flowing with such force, shattering barriers in its path, flows the new stream. Come, bathe with me there, holding on to my arms as your floats!

79 Stranger in the stream

‘புதுப் புனல் ஆடி அமர்த்த கண்ணள்,

யார் மகள், இவள்?’ எனப் பற்றிய மகிழ்ந!

யார் மகளாயினும் அறியாய்;

நீ யார் மகனை, எம் பற்றியோயே?

O lord of the town, you caught hold of her hand, and asked, ‘Playing in the fresh stream, your eyes are reddened, whose daughter are you?’ You know not whose daughter she is. So tell me, whose son are you, that you clasp her hand without even knowing her?

80 Reddened in the river

புலக்குவெம் அல்லேம்; பொய்யாது உரைமோ:

நலத்தகு மகளிர்க்குத் தோள் துணை ஆகி,

தலைப் பெயல் செம் புனல் ஆடித்

தவ நனி சிவந்தன, மகிழ்ந! நின் கண்ணே.

I’m not going to get furious; So tell me without lying; You have offered your arms as companions to beautiful maiden and played in the gushing red stream that flows after the first rains, for your eyes are really reddened now, O lord!

And thus concludes Ainkurunooru 71-80. All these verses without an exception are set in the context of the man’s love quarrels with the lady, after marriage, owing to his association with courtesans. The unifying element in each of these verses is the act of bathing together in the river stream. These verses are rendered by different speakers and we will explore the same as we go along.

In the first, the lady is angered by news of the man’s bathing with the courtesan and she says to him that he cannot lie to her because no one can hide gossip just as no one can mask the brightness of the sun. In the next three verses, the man reminisces to the confidante about the time when the lady bathed with him during their love relationship phase, so as to calm the listening lady and invite her to bathe with him now. He talks about all her alluring features and how she readily became his companion as the river stream came gushing with flowers. In another, he relates how the stream became cooler and seemed to take on the scent of blue-lilies, just because the lady plunged into the waters. In the final one in this sub-section, the man recollects how the image of descending peacock feathers from the sky appeared before his eyes, when the lady climbed on to an Arjuna tree by the shore and jumped into the waters from there. What sweet talk on the part of the man! Would the lady be floored with these nostalgic words rendered?

Seems not, for in the fifth, the confidante goes back to theme of the lady’s anger, incited by the man’s playing with the courtesan, and owing to this, the man has become dishonourable in the eyes of many in town. In the sixth too, she talks of how just because the courtesan played with the man in the stream, she seemed to attain so much beauty that angels above thought she was a god spirit of the waters.

In the seventh verse, the spotlight falls on the courtesan as she tells the man, ‘Let’s go bathe without caring about rumours any. Just do one thing for me. Please do not go back to your home and to your wife’. In the eighth too, she uses a simile containing historical elements, reminding us of the Puranaanooru verses, we recently bid bye to, mentioning about how the elephants of King Killi strike against and shatter fort walls, and like that the gushing stream too flows with such force that it breaks any obstacles in its bath. It’s in this stream that she invites the man to play with her. That image of the river stream that breaks barriers and flows with force is the only metaphorical element in these ten verses, and here, the courtesan places it as a metaphor for how the man’s return to the lady will destroy her relationship with the man, and intends to keep that at bay with her invitation to the man to bathe with her.

The ninth verse is set in the curious context of the man bathing alone in the stream, and hearing of this, the courtesan too bathes alone. At this time, wanting to appease her, the man seems to have caught hold of her and pretended to ask who she was. The courtesan’s confidante repeats this incident to the man and asks jokingly, whose son was he that he had the audacity to clasp the hand of someone he knew not. A variation of the ‘Hello, stranger’ line, we have seen in many movies said to a known and intimate character!

In the final verse, the verse comes a full circle and the lady asks the man to tell the truth about whether he was playing in the fresh river stream after the first rains with beautiful women, for she could see that his eyes were a deep red.

And so, we see in verse after verse, the role that the act of bathing played in the life of these Sangam people. It’s not just a daily ritual that many of us indulge in so mindlessly in this machine-age! This was something that seemed to carry so much significance to their emotions and relationships. This reminds me of how in many urban civilisations of the past, provisions would be made for communal bathing. The Great Bath of Mohenjadaro comes first to mind. As does the Greek and Roman baths that we have heard so much about! That no doubt arose from this culture of bathing in waterbodies, and given that civilisations arose on the banks of rivers, this comes as no surprise. From the angle of the Sangam era, it was delightful to read descriptions of rivers rushing with flowers and freshness after the first rains. In a nutshell, if we can set aside the jagged rock edges of these squabbles, it’s a refreshing dip into the rejuvenating flow of the past!