Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | iHeartRadio | TuneIn | RSS | More

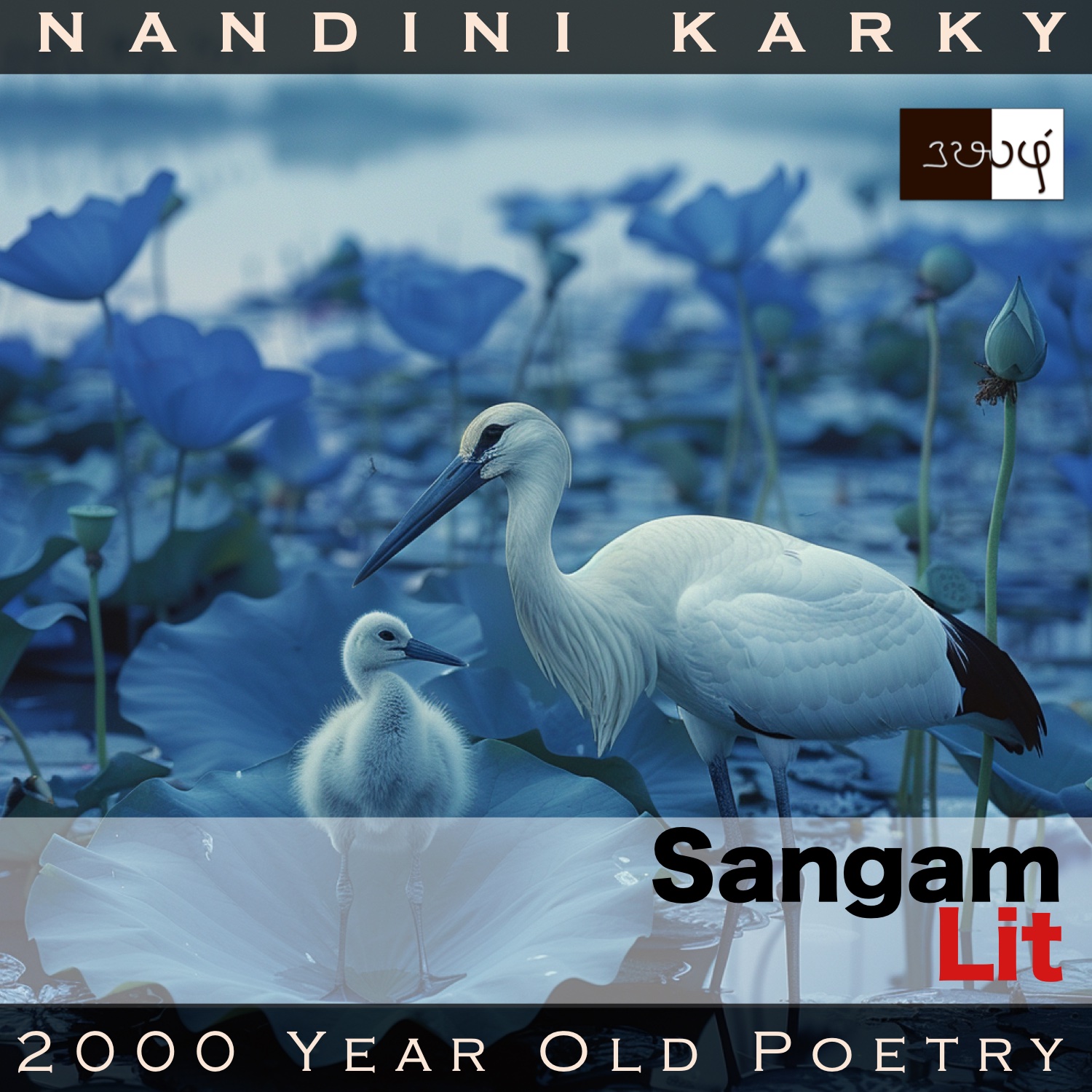

In this episode, we perceive the allegorical actions of a stork and a white seabird chick, as depicted in Sangam Literary work, Ainkurunooru 151-160, situated in the ‘Neythal’ or ‘Coastal landscape’ and penned by the poet Ammoovanaar.

Here goes the Sixteenth Ten of Ainkurunooru: Case of Mistaken Indentity

151 Blooming blue lotus

வெள்ளாங்குருகின் பிள்ளை செத்தென,

காணிய சென்ற மட நடை நாரை

மிதிப்ப, நக்க கண் போல் நெய்தல்

கள் கமழ்ந்து ஆனாத் துறைவற்கு

நெக்க நெஞ்சம் நேர்கல்லேனே.

When the stork with a naive gait went to see the white seabird’s chick, thinking the chick was its own, it stepped on a blue lotus, making the bud spread open its petals and look like eyes wide open. The fragrance of the flower’s sweet nectar then spread unceasingly in the lord’s shore. As my heart is broken, I cannot accept this request and allow him entry.

152 Helpless cry

வெள்ளாங்குருகின் பிள்ளை செத்தென,

காணிய சென்ற மட நடை நாரை

கையறுபு இரற்று கானல்அம் புலம்பந்

துறைவன் வரையும் என்ப;

அறவன் போலும்; அருளுமார் அதுவே.

When the stork with a naive gait went to see the white seabird’s chick, thinking the chick was its own, it called out with helplessness in the groves of the lord’s shore. They say he will marry her; Indeed he’s a man of justice, who never fails to shower his graces.

153 Falling feathers

வெள்ளாங்குருகின் பிள்ளை செத்தென,

காணிய சென்ற மட நடை நாரை

உளர, ஒழிந்த தூவி குவவு மணல்

போர்வில் பெறூஉம் துறைவன் கேண்மை

நல்நெடுங் கூந்தல் நாடுமோ மற்றே?

When the stork with a naive gait went to see the white seabird’s chick, thinking the chick was its own, it was pecked and the feathers it shed fell on the sand heaps, waiting to be picked in the lord’s shore. Will the one, with fine, long tresses, accept his relationship anymore?

154 The bird that stayed

வெள்ளாங்குருகின் பிள்ளை செத்தென,

காணிய சென்ற மட நடை நாரை

கானல் சேக்கும் துறைவனோடு

யான் எவன் செய்கோ? பொய்க்கும் இவ் ஊரே?

When the stork with a naive gait went to see the white seabird’s chick, thinking the chick was its own, it stayed in the grove of the lord’s shore. What am I to do, in this town of lies?

155 Washed away by the waves

வெள்ளாங்குருகின் பிள்ளை செத்தென,

காணிய சென்ற மட நடை நாரை

பதைப்ப, ததைந்த நெய்தல் கழிய

ஓதமொடு பெயரும் துறைவற்குப்

பைஞ்சாய்ப் பாவை ஈன்றனென், யானே!

When the stork with a naive gait went to see the white seabird’s chick, thinking the chick was its own, it fluttered its wings and crushed the blue lotus and these flowers washed away in the waves of the lord’s shore. I have borne him a child, made of sedge grass already!

156 Fluttering feathers

வெள்ளாங்குருகின் பிள்ளை செத்தென,

காணிய சென்ற மட நடை நாரை

பதைப்ப, ஒழிந்த செம் மறுத் தூவி

தெண் கழிப் பரக்கும் துறைவன்

எனக்கோ காதலன்; அனைக்கோ வேறே!

When the stork with a naive gait went to see the white seabird’s chick, thinking the chick was its own, it fluttered its wings, making its red-lined feathers scatter in the the lord’s shore, with cool backwaters. To me, he appears loving, but to my friend, he appears different.

157 All day stay

வெள்ளாங்குருகின் பிள்ளை செத்தென,

காணிய சென்ற மட நடை நாரை

காலை இருந்து மாலைச் சேக்கும்

தெண் கடற் சேர்ப்பனொடு வாரான்,

தான் வந்தனன், எம் காதலோனே!

When the stork with a naive gait went to see the white seabird’s chick, thinking the chick was its own, it stayed there from morning to evening in the lord’s shore, with clear seas. Without returning with him, alone he comes, my loving son!

158 Roaming with the mate

வெள்ளாங்குருகின் பிள்ளை செத்தென,

காணிய சென்ற மட நடை நாரை

கானல்அம் பெருந் துறைத் துணையொடு கொட்கும்

தண்ணம் துறைவ! கண்டிகும்,

அம் மா மேனி எம் தோழியது துயரே.

When the stork with a naive gait went to see the white seabird’s chick, thinking the chick was its own, it forgot that and roamed with its mate in the groves of the lord’s great and cool shore. Why don’t you go and allay the sorrow of our friend with a beautiful form, akin to a tender mango shoot?

159 Hungry bird

வெள்ளாங்குருகின் பிள்ளை செத்தென,

காணிய சென்ற மட நடை நாரை

பசி தின, அல்கும் பனி நீர்ச் சேர்ப்ப!

நின் ஒன்று இரக்குவென் அல்லேன்;

தந்தனை சென்மோ கொண்ட இவள் நலனே?

When the stork with a naive gait went to see the white seabird’s chick, thinking the chick was its own, it felt hungry and stayed in the lord’s shore, filled with the cool waves. I don’t seek anything else from you. Just give back the health and beauty you stole from her!

160 Swelling sadness

வெள்ளாங்குருகின் பிள்ளை செத்தென,

காணிய சென்ற மட நடை நாரை

நொந்ததன் தலையும் நோய் மிகும் துறைவ!

பண்டையின் மிகப் பெரிது இனைஇ,

முயங்குமதி, பெரும! மயங்கினள் பெரிதே!

When the stork went to see the white seabird’s chick, thinking the chick was its own, it lamented and its distress swelled in the lord’s shore. Even more than the past, go and embrace her and shower your graces, O lord, for she seems to be distressed greatly.

Thus concludes Ainkurunooru 151-160. All the songs are set in the context of a man’s married relationship with the lady, and specifically, in the situation of a love quarrel involving the courtesan. The unifying theme in all these verses is an allegorical depiction of a stork going to see a white seabird’s chick, thinking the little one was its own. This is supposed to imply the situation of a man visiting and living with the courtesan as if she were his rightful mate, the lady, and abandoning the lady in the process. These verses are said either by the lady or the confidante to each other or to the man or his messengers, seeking entry to the lady’s home.

In the first, the lady declares her heart is broken and she cannot accept the man back, when pressed by her confidante. In the second too, in reply to the confidante’s words that although the man has done a wrong thing, he is a good person and full of love for the lady, the lady replies in anger that she had heard about the man’s intention to marry the courtesan, and asks her friend, ‘Is this what you call justice and love?’. In the third, the confidante relays this message of refusal from the lady to the man’s messengers saying, ‘In this situation how can the beautiful lady accept the man again?’.

In the fourth, it’s the lady back in the spotlight as she accuses the town of lying about the man’s goodness and wonders what she is to do in such a town. This is in response to the confidante’s message to her asking the lady to accept the man. In the fifth, the confidante tries to remind her of her wifely duties of giving birth to the man’s child, and in response, the lady says, when they were in a love relationship, she bore him a child in the form of a doll, made of sedge grass. That will do for him, she says, in anger! This strong refusal etches the character of the lady with strength and clarity. In the sixth, it’s the confidante back again and she refuses entry to the man’s messengers saying, ‘I can see that he’s loving but my friend doesn’t think so, and so, no!’.

The seventh reveals a curious situation when the man seems to have taken his son along to the courtesan’s house, and he then decides to stay there, making the child return on his own. It’s this sad state of affairs that the lady remarks about. In the eighth, the confidante says sarcastically to the man that instead of coming home since the courtesan was angry with him, the man should go there and end her sorrow. In the next too, the confidante tells the man, ‘I just want one thing from you and that’s for you to return the lady’s health and beauty that you stole from her!’. In the final one, the lady is back to the spotlight and full of sarcasm, asking the man to go back to the courtesan and even more than ever, show his love to her and cure her ire.

Looking at some of the the metaphorical elements in addition to the core allegory of the stork and the white seabird’s chick, we find images like the blue lotus opening up because the stork steps on it, and spreading its nectar, which is a metaphor for the man’s actions opening the mouths of the town’s people, and their spreading of gossip. In another one, the falling feathers lying in heaps on the shore indicate the money and wealth showered by the man on the courtesans. Then, there’s the easy one, where the stork stays back in the white seabird’s place, and that’s a simple metaphor for the man not returning home from his visit to the courtesans. In the image of the blue lotus being swept away by the waves, there’s a metaphor for the man returning to his wife, because of the elders’ words, and then again going back to the courtesan, pulled by the wave of her attraction.

Yet again, it’s the conflicts of the ‘Marutham’ landscape repeating in the seashore. This allegory of the stork mistaking another chick for its own made me wonder if this really happens in nature. There’s the case of the cuckoo laying its eggs in a crow’s nest and fooling the crow. However, other than this one instance, this sort of confusion does not really seem prevalent. This is because birds are so skilled in identifying their young ones with their unique calls and will always go feed their own chicks. Perhaps looking at the young ones of birds and the wandering parents of these birds, which travel far and bring back food, perhaps Sangam people wondered, ‘Won’t these birds get confused ever?’, and possibly this particular section arose out of such a thought. It would only be a case of underestimating the intelligence of birds and animals, and this thought reminded me of a specific research article that I recently read, about how elephants call their young and other members of their group with a unique voice call, equivalent to the ‘names’ we give people. That’s a stunning discovery and tells us never to think less of the emotions or intelligence of the other kinds of life around us!