Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | iHeartRadio | TuneIn | RSS | More

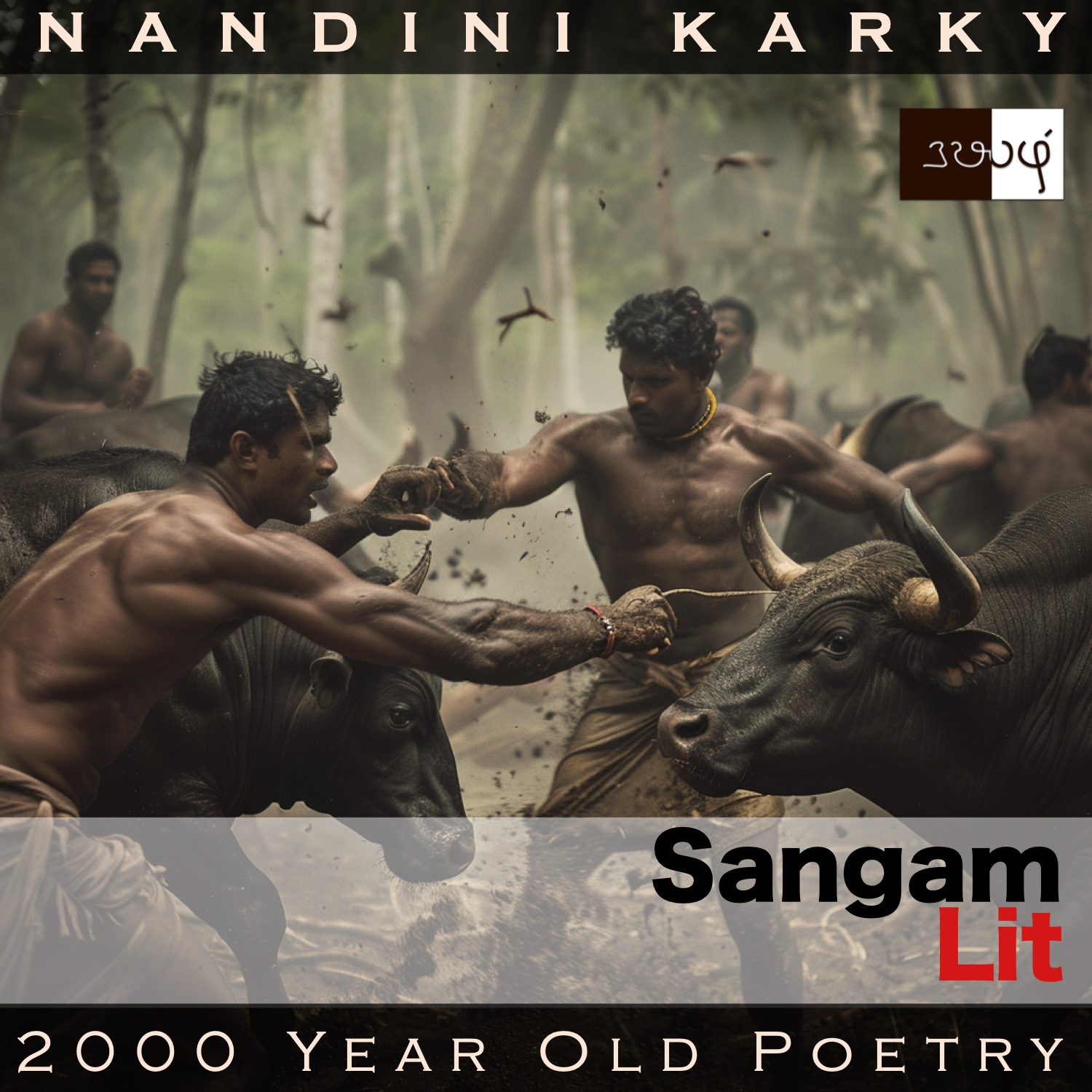

In this episode, we perceive the practical aspects of bull taming, as portrayed in Sangam Literary work, Kalithogai 106, penned by Chozhan Nalluruthiran. The verse is situated in the ‘Mullai’ or ‘Forest Landscape’ and reveals the value of courage in a man, as seen from the eyes of their beloved maiden.

ஏறு கோடல்

கழுவொடு சுடு படை சுருக்கிய தோற்கண்,

இமிழ் இசை மண்டை உறியொடு, தூக்கி,

ஒழுகிய கொன்றைத் தீம் குழல் முரற்சியர்,

வழூஉச் சொற் கோவலர், தத்தம் இன நிரை

பொழுதொடு தோன்றிய கார் நனை வியன் புலத்தார்

அவ்வழி,

நீறு எடுப்பவை, நிலம் சாடுபவை,

மாறு ஏற்றுச் சிலைப்பவை, மண்டிப் பாய்பவையாய்

துளங்கு இமில் நல் ஏற்றினம் பல களம் புகும்

மள்ளர் வனப்பு ஒத்தன

தாக்குபு தம்முள் பெயர்த்து ஒற்றி, எவ் வாயும்,

வை வாய் மருப்பினான் மாறாது குத்தலின்,

மெய் வார் குருதிய ஏறு எல்லாம் பெய் காலைக்

கொண்டல் நிரை ஒத்தன

அவ் ஏற்றை,

பிரிவு கொண்டு, இடைப் போக்கி, இனத்தோடு புனத்து ஏற்றி,

இரு திறனா நீக்கும் பொதுவர்

உரு கெழு மா நிலம் இயற்றுவான்

விரி திரை நீக்குவான் வியன் குறிப்பு ஒத்தனர்

அவரை, கழல உழக்கி, எதிர் சென்று சாடி,

அழல் வாய் மருப்பினால் குத்தி, உழலை

மரத்தைப் போல் தொட்டன ஏறு

தொட்ட தம் புண் வார் குருதியால் கை பிசைந்து, மெய் திமிரி,

தங்கார் பொதுவர் கடலுள் பரதவர்

அம்பி ஊர்ந்தாங்கு, ஊர்ந்தார் ஏறு

ஏறு தம், கோலம் செய் மருப்பினால் தோண்டிய வரிக் குடர்

ஞாலம் கொண்டு எழூஉம் பருந்தின் வாய் வழீஇ,

ஆலும் கடம்பும் அணிமார் விலங்கிட்ட

மாலை போல் தூங்கும் சினை

குரவை ஆடுதல்

ஆங்கு,

தம் புல ஏறு பரத்தர உய்த்த தம்

அன்பு உறு காதலர் கை பிணைந்து, ஆய்ச்சியர்

இன்புற்று அயர்வர் தழூஉ

முயங்கிப் பொதிவேம்; முயங்கிப் பொதிவேம்;

முலை வேதின் ஒற்றி, முயங்கிப் பொதிவேம்

கொலை ஏறு சாடிய புண்ணை எம் கேளே!

பல் ஊழ் தயிர் கடையத் தாஅய புள்ளி மேல்

கொல் ஏறு கொண்டான் குருதி மயக்குறப்

புல்லல் எம் தோளிற்கு அணியோ? எம் கேளே!

ஆங்கு, போர் ஏற்று அருந் தலை அஞ்சலும், ஆய்ச்சியர்

காரிகைத் தோள் காமுறுதலும், இவ் இரண்டும்

ஓராங்குச் சேறல் இலவோ? எம் கேளே!

‘கொல் ஏறு கொண்டான், இவள் கேள்வன்’ என்று, ஊரார்

சொல்லும் சொல் கேளா, அளை மாறி யாம் வரும்

செல்வம் எம் கேள்வன் தருமோ? எம் கேளே

தென்னன் வாழ்க பாடுதல்

ஆங்க,

அருந் தலை ஏற்றொடு காதலர்ப் பேணி,

சுரும்பு இமிர் கானம் நாம் பாடினம் பரவுதும்

ஏற்றவர் புலம் கெடத் திறை கொண்டு,

மாற்றாரைக் கடக்க, எம் மறம் கெழு கோவே!

A song that’s different from the previous series of bull taming verses in a significant way. The words can be translated as follows:

“Bull Taming

Along with the cattle prod, a kindling stick is tied within a draw-string leather bag and food bowls that bang against each other hang on the hoops. Carrying all this and playing on the sweet flute, made from a long and dried-up pod of the golden shower tree, the herders known for their quirky diction, walked on to the wide forest spaces, moistened by the seasonal rains, along with their herds of cattle.

In that place, some bulls that were used to stirring up the dust, muddied the moistened ground now, some bellowed with hostility and some crouched to pounce on their opponents. Those sturdy bulls with radiant humps appeared with the handsome quality of warriors entering the battlefield.

They attacked each other and pushed them apart, and since sharp horns had pierced ceaselessly, the blood that poured from their bodies made the bulls resemble a gathering of clouds, pouring with rain.

The herders there, who separated those bulls, created spaces in between, moved them to the meadows into two groups, appeared akin to the One, who created the vast and expansive land with immense thoughtfulness by separating the roaring waves.

In that process, the bulls scattered the herders by pouncing from behind, attacking them from the front, stabbing them with their fire-like horns and made the herders appear like wooden doors with holes in them. Rubbing away the pouring blood from the wounds made by these piercing bulls, shaking their bodies, the herders keep moving, akin to fishermen riding their boats in the seas. The lined intestines pulled out by the well-adorned horns of the bulls are carried away by birds of prey in the sky. The image of those intestines hanging from the bird’s mouth appears akin to a branch on which hangs a glowing garland, left there to adorn the spirits residing in the banyan and the burflower!

Kuravai Dancing:

And so, holding the hands of their lovers after they have left the bulls to graze in the meadows, the maiden dance together with them, embracing with joy.

“All those wounds on my beloved made by those killer bulls, with an embrace, let me bury; with an embrace, let me bury; Caressing with the warmth of my bosom, with an embrace, let me bury! My love’s wounds!

On those spots that have spread on my arms when churning the curd, when the blood of the one who tamed the bull fuses together as we embrace, doesn’t that adorn my arms so? My love’s embrace!

And so, fearing the frightening head of the battling bull and desiring the picturesque arms of a herder maiden never ever go together, would they? Oh my love!

Won’t my love render me much more wealth than I earn by selling curd, when I hear the townsfolk praise him saying, ‘Her lover tamed a killer bull’? Oh my love!

Praising the King:

And so, guarding our beloved and the precious bulls, let’s sing and pray to the bee-buzzing forest, wishing that our courageous king gathers tributes, ruining the land of his opponents, and conquers his enemies forever and ever!”

Time to explore the nuances. The verse is situated in the context of bull taming and its relevance to winning the hand of a maiden and these words are rendered by a narrator, depicting the events and conversations that unfold in this landscape. First, we perceive the objects that are carried by a herder in the forests, and these are, as expected, a cattle prod, to keep those animals in check, a kindling stick for those freezing evenings, and then, food bowls to make a meal on the go. Food for the stomach taken care of, but what about the food for the soul? For this, these clever herders turn the dried-up pods of the golden shower tree into flutes rendering sweet music. The scene changes and now we see these herders walking with their cattle towards the moistened grounds of the forest. Then, we hear an account of the bulls getting into a fierce fight with each other, appearing like some warriors in the field. As they gore the bodies of each other, they seem to look like clouds, pouring with rain. Now, the herders intervene and try to push the cattle apart, separate the fighting groups, and this is connected to the interesting simile of a creator, who decides to carve land amidst the roaring seas and pushes apart the waves. Even though there’s a creator myth in this belief, what I liked about it was the understanding that the oceans preceded land in the timeline of the world. Now, the bulls are mad at the herders and pounce at them with rage, piercing them with their horns, but the herders don’t seem to mind it at all, and rubbing away the blood pouring from their wounds, they keep walking on, with their cattle, appearing like fishermen in a boat, riding on the sea. A gory image of intestines pulled out from the men and picked up by an eagle or a vulture is connected to a divine element – a garland placed on trees like the banyan and the burflower, which we have read in an earlier verse that the bull tamers pray to!

After summing those scenes of bull taming, the narrator moves on to give an account of the Kuravai dance of maiden and the content of their songs. The maiden vow to heal the wounds of their men, who have bravely defended against the bulls, with the warmth of their embraces. They delight in the fusing of the white spots on their forms, which has appeared owing to their churning of curd, an important occupation for women of this landscape, and the blood gushing from the bull tamers. There’s no way love for a herder daughter and fear for a bull can go hand in hand, they declare. The dancers also talk about how the greatest wealth for a herder woman is to hear the townsfolk praise her beloved for his prowess in taming a bull. Finally, the maiden end their dance by pledging to protect their bulls and their men, and praying to the forest, wishing for their king’s forever victory!

The striking aspect of this verse is in the fact that the bull taming happens in the real world. As we saw in the beginning, the skills of the men in controlling those bulls was not just for sport or to win the hand of their beloved maiden, this was something much-needed in their everyday life. Not only for glory or love, do these men dare to fight the bulls but for their very livelihood! Wouldn’t it be the right thing if exams and education in the modern era, rather than testing memory or recall, trains the students for exactly what they need in their lives, like our ancient ancestors in that wild arena?