Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | iHeartRadio | TuneIn | RSS | More

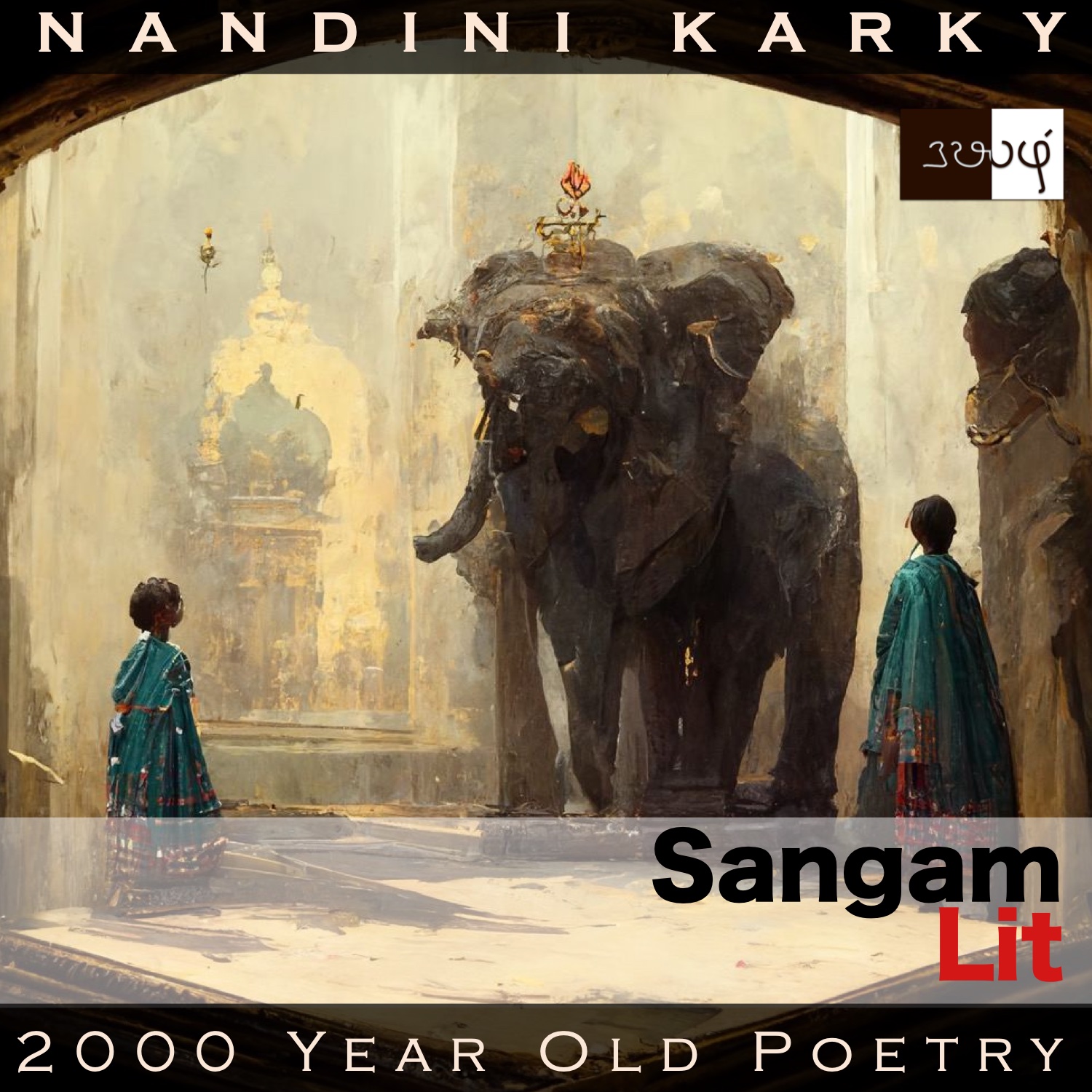

In this episode, we witness a rendition of heart-rending words, as portrayed in Sangam Literary work, Puranaanooru 46, sung to the Chozha King Kulamutrathu Thunjiya Killivalavan by the poet Kovoor Kizhaar. The verse is situated in the category of ‘Vanji Thinai’ or ‘king’s prowess in the battlefield’ and argues against an atrocious act about to be committed.

நீயே, புறவின் அல்லல் அன்றியும், பிறவும்

இடுக்கண் பலவும் விடுத்தோன் மருகனை,

இவரே, புலன் உழுது உண்மார் புன்கண் அஞ்சி,

தமது பகுத்து உண்ணும் தண் நிழல் வாழ்நர்;

களிறு கண்டு அழூஉம் அழாஅல் மறந்த

புன் தலைச் சிறாஅர்; மன்று மருண்டு நோக்கி,

விருந்தின் புன்கண் நோவுடையர்;

கேட்டனைஆயின், நீ வேட்டது செய்ம்மே!

The focus shifts once again to the much sung about Chozha king Killivalavan, at the time when he had battled with and defeated another king Malaiyamaan. Let’s delve into the situation after we have assimilated the poet’s words, which can be translated as follows:

“You are the descendant of the one, who not only allayed the suffering of a dove, but the sorrows of many others too. Whereas, they lived in the cool shade of the generous, who share what they have with those, who live by ploughing their talents, fearing that otherwise these men of wisdom would live a life of suffering. They are mere sparse-haired children, who even forget that they should cry upon seeing the elephant. As they look at the gathered assembly with confusion, there’s a never-before suffering in their eyes. If you have fully heard what I have said… go ahead and do what you want to do!”

Now, for the details in this song, which is somewhat hard to grasp at first glance! The poet starts by talking about the ancestors of this king, linking back to the story of King Sibi and the dove, and mentions not only did that ancestor give away his own flesh to end the suffering of that bird, but he has erased the sorrows of many others. Then, the poet turns to the subjects under discussion and we understand that they are the young children, who have grown up in the shade of someone, kind enough to have shared his wealth with those who are said to live by ‘ploughing their talents’. A curious title for poets and scholars, who have only their minds to plough on and produce. By this, the poet means the parents of those children have been patrons of poets and he lauds their generosity.

Who are these parents and why are these children being talked about now? The answer to this question lies in the context of the song. As we saw before, the Chozha king Killivalavan had conquered another king Malaiyaaman and it’s this Malaiyaaman being talked about as being that generous patron to scholars in the land. The children are his children and the moment when this song is being sung is when the Chozha king decides to put to death, those innocent children of Malaiyamaan, by the stamping of elephants. A shudder runs through the spine at the prospect of such cruelty, which was commonplace in that ancient world of royal rivalry! At this juncture, the poet points out how the children forget even to cry upon seeing the approaching elephants and how they are looking around in bewilderment at the gathered crowds, a new distress in their eyes. After painting that poignant scene, the poet ends with the message that the king may do what he wishes after fully taking in the weight of these words.

And, what weight indeed these few words seem to have, for it’s the lives of young children that’s being talked about! The poet presents his argument in a brilliant manner, evoking first images of compassion in the king’s ancestor. ‘Here’s your predecessor, who thought of the suffering of a little bird, won’t you find even a shred of that kindness within you’, the poet seems to ask without asking. At the same time, the poet presents the good nature of the king’s opponent. ‘He may be your enemy and you may see him as evil because he opposes you but there is good in him’, the poet subtly points out. And finally, he paints a striking portrait of the children’s innocence and vulnerability. Thereby, he makes it impossible for anyone with a heart to ignore their plight.

In that finishing line is a communication style deeply ingrained in Tamil culture that lives on to this very day. Many a Tamil would have heard this line in their lifetime from one person or the other – ‘Naan solratha solliten. Nee enna venumo senjuko’, which can be translated as ‘I have said what I have to say. You do what you want to do.’ Here, instead of ordering the listener to do or not do something, the technique is to present the facts and then leave it to them to take that decision. Isn’t that an empowering way of changing someone’s heart? And thus, in more ways than one, the verse demonstrates the impact of words in not just informing and entertaining but also, saving lives!