Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | iHeartRadio | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

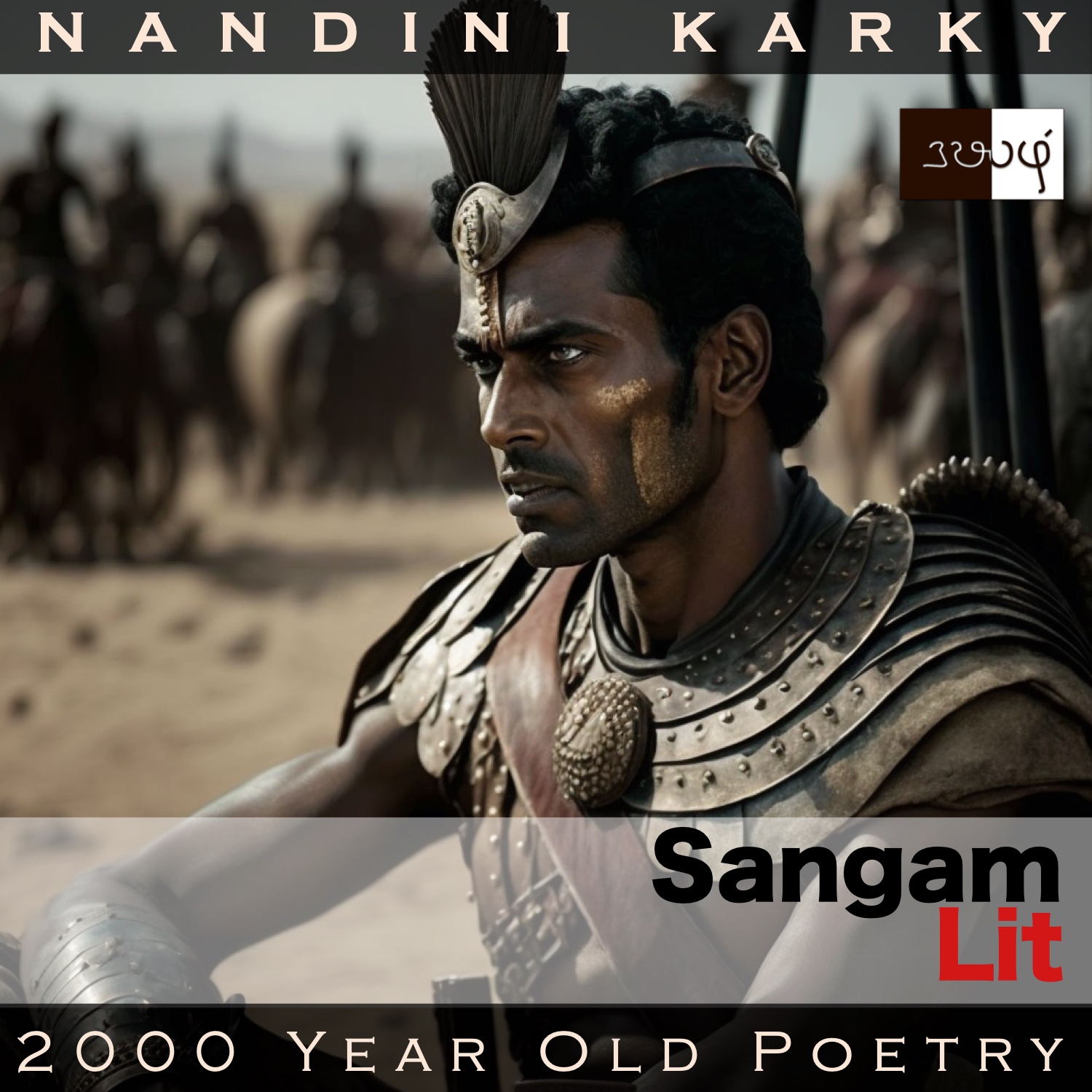

In this episode, we learn of courage and death in an ancient battlefield, as depicted in Sangam Literary work, Puranaanooru 93, penned about the Velir King Athiyamaan Nedumaan Anji, by the poet Avvaiyaar. Set in the category of ‘Vaagai Thinai’ or ‘King’s victory’, the verse sketches the honourable conquest of this king at war.

திண் பிணி முரசம் இழுமென முழங்கச்

சென்று, அமர் கடத்தல் யாவது? வந்தோர்

தார் தாங்குதலும் ஆற்றார், வெடிபட்டு,

ஓடல் மரீஇய பீடு இல் மன்னர்

நோய்ப்பால் விளிந்த யாக்கை தழீஇ,

காதல் மறந்து, அவர் தீது மருங்கு அறுமார்,

அறம் புரி கொள்கை நான்மறை முதல்வர்

திறம் புரி பசும் புல் பரப்பினர் கிடப்பி,

‘மறம் கந்தாக நல் அமர் வீழ்ந்த

நீள் கழல் மறவர் செல்வுழிச் செல்க!’ என

வாள் போழ்ந்து அடக்கலும் உய்ந்தனர் மாதோ

வரி ஞிமிறு ஆர்க்கும் வாய் புகு கடாஅத்து

அண்ணல் யானை அடு களத்து ஒழிய,

அருஞ் சமம் ததைய நூறி, நீ,

பெருந் தகை! விழுப் புண் பட்ட மாறே.

A verse that renders nuanced details about customs in war. The poet’s words can be translated as follows:

“How is it possible any more to win over enemies, as well-tied drums resound aloud? For those who came, unable to bear the attack of your vanguard, scattered and ran away. And thus, those kings perished without honour. Embracing those diseased bodies, ignoring any kindness they felt, to make the sins of the fallen vanish, those priests well-versed in the four scriptures that endow justice, spread them on lush, green grass. Then, saying the words, “With the sole foundation of your courage to battle, may you part in the path of warriors wearing long anklets, who receive an honourable death in the field’, the priests sliced them with swords and avoided the dishonour of a common burial! Only because you, O great lord, who, in that formidable battlefield, has the great strength to slay imposing elephants in musth, around which stripped bees buzz around, is now covered with battle wounds many!”

Let’s delve into this somewhat cryptic verse! The poet begins with a rhetorical question about how any further victories are possible. Then, she goes on to explain the reasoning for that question talking about how all the attacking enemies were scattered, unable to bear the assault of King Athiyamaan’s army and had run away from the field and perished. Instead of a burial that was mandated for warriors who did not die a courageous death on the field, they were given an honourable death by priests, who laid them on lush, green grass and ended their lives with a sword, saying the words of prayer that they too shall walk the path of brave, anklet-clad warriors, because they had the courage to battle. The poet first describes King Athiyamaan as a slayer of elephants in musth – something unsavoury to us in the present but probably, a significant marker of the king’s valour in the battlefield. She concludes how the death given to those enemies by priests was acceptable only because this Velir King too suffered battle wounds at their hands, implying that they had put up a brave fight at least initially.

This verse reminded me so much of bravado at the end of a fight that we have seen on screen at least. A person who’s been in a fight with another and ends up with cuts and wounds would remark, ‘My wounds are nothing. You should see him’, thereby claiming that they have vanquished their opponent. That’s the same effect the poet renders in this verse, by justifying the honourable deaths of those who fled the battle scene, because of the wounds inflicted by them on this king. The importance wars and victories commanded in their lives is illustrated herein!

Share your thoughts...