Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | iHeartRadio | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

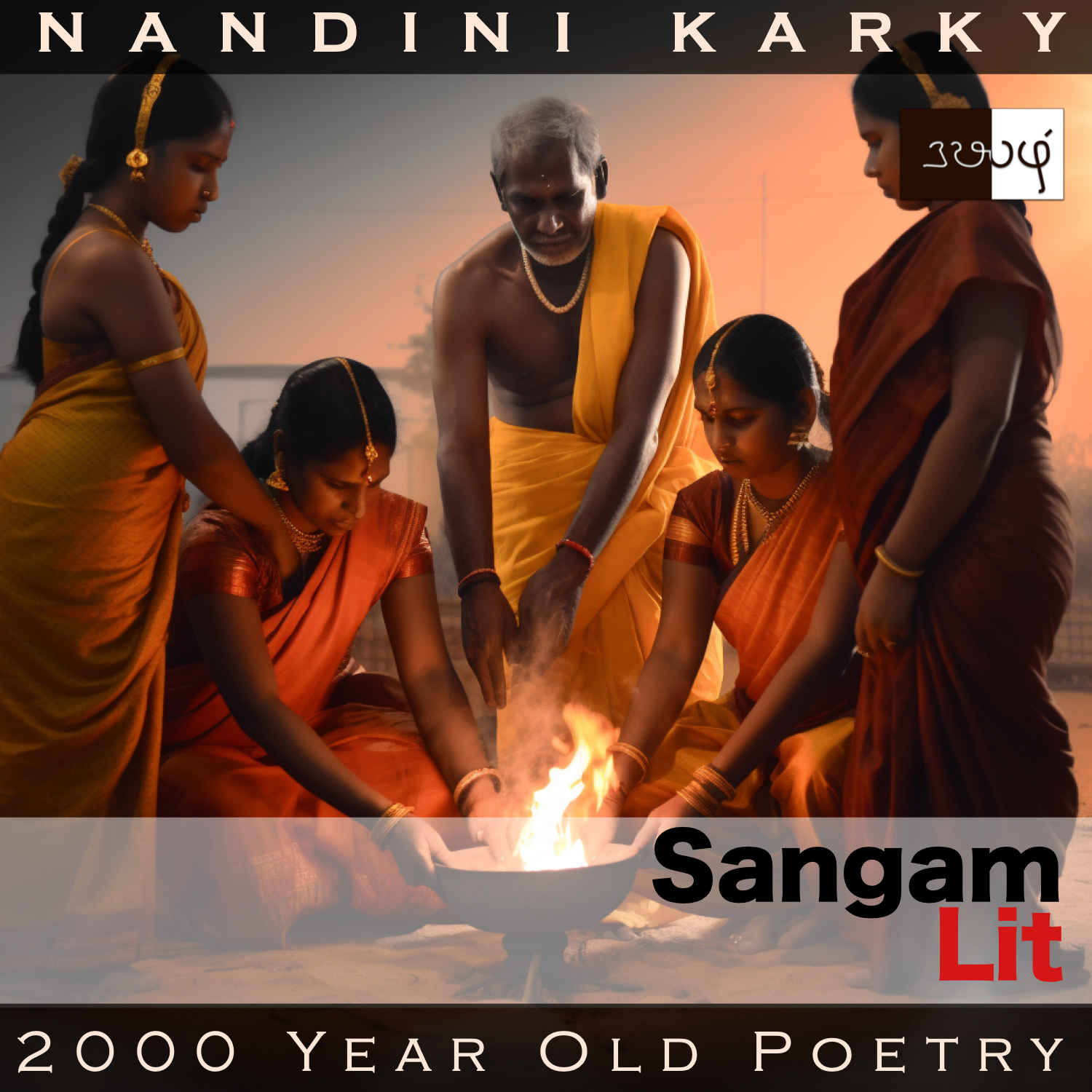

In this episode, we listen to an account of religious rituals, as depicted in Sangam Literary work, Puranaanooru 166, penned about a priestly man Sonaattu Poonchaatroor Paarpaan Kouniyan Vinnanthaayan by the poet Aavoor Moolankizhar. Set in the category of ‘Vaagai Thinai’ or ‘Victory’, the verse talks about the triumph of one belief system over another.

நன்று ஆய்ந்த நீள் நிமிர் சடை

முது முதல்வன் வாய் போகாது,

ஒன்று புரிந்த ஈர் இரண்டின்,

ஆறு உணர்ந்த ஒரு முது நூல்

இகல் கண்டோர் மிகல் சாய்மார்,

மெய் அன்ன பொய் உணர்ந்து,

பொய் ஓராது மெய் கொளீஇ,

மூ ஏழ் துறையும் முட்டு இன்று போகிய

உரைசால் சிறப்பின் உரவோர் மருக!

வினைக்கு வேண்டி நீ பூண்ட

புலப் புல்வாய்க் கலைப் பச்சை

சுவல் பூண் ஞாண்மிசைப் பொலிய;

மறம் கடிந்த அருங் கற்பின்,

அறம் புகழ்ந்த வலை சூடி,

சிறு நுதல், பேர் அகல் அல்குல்,

சில சொல்லின், பல கூந்தல், நின்

நிலைக்கு ஒத்த நின் துணைத் துணைவியர்

தமக்கு அமைந்த தொழில் கேட்ப;

காடு என்றா நாடு என்று ஆங்கு

ஈர் ஏழின் இடம் முட்டாது,

நீர் நாண நெய் வழங்கியும்,

எண் நாணப் பல வேட்டும்,

மண் நாணப் புகழ் பரப்பியும்,

அருங் கடிப் பெருங் காலை,

விருந்துற்ற நின் திருந்து ஏந்து நிலை,

என்றும், காண்கதில் அம்ம, யாமே! குடாஅது

பொன் படு நெடு வரைப் புயலேறு சிலைப்பின்,

பூ விரி புது நீர்க் காவிரி புரக்கும்

தண் புனல் படப்பை எம் ஊர் ஆங்கண்,

உண்டும் தின்றும் ஊர்ந்தும் ஆடுகம்;

செல்வல் அத்தை, யானே; செல்லாது,

மழை அண்ணாப்ப நீடிய நெடு வரைக்

கழை வளர் இமயம் போல,

நிலீஇயர் அத்தை, நீ நிலம்மிசையானே.

A long song describing the background and process of a Vedic ritual in Sangam times. The poet’s words can be translated as follows:

“Never swerving from the deeply studied word of the ancient god with long, matted locks of hair, and aiming to reduce the numbers of those who disagree with the ancient book of righteousness, expressing the same thought through four volumes, and understanding their falsehoods that seem like truth, not accepting those falsehoods and instead to convey the truth to others, your ancestors completed 21 sacrifices, O esteemed descendant!

For the ritual, you have covered yourself with the skin of a male deer that grazes in the forest, and this glows atop the white thread across your shoulders. With a virtue devoid of severity, wearing the holy ornament prescribed by the scriptures, with a small forehead, wide hips, of few words and copious tresses, your companion women, who are of one mind with your state, render their duties in fourteen different venues which cannot be called a forest or a town. You pour ghee putting water to shame, perform rituals putting numbers to shame, spread your religion’s fame across lands numerous. This elegant state with which you rendered your feast, I happened to witness. Long may you live!

In the gold-hued mountains on the west, where stormy clouds roar, flower-coated fresh waters of the Kaveri spring forth, and to my village there flowing with these cool waters, drinking, eating and riding, I shall go; Akin to the tall mountains of the bamboo-abounding Himalayas, which rainclouds, unable to cross, look up in awe, may your fame stand strong on earth for long!”

Let’s explore the details presented here. The poet addresses a priest through this verse and talks about the theology of this religion, which believes in the word of an ancient God with long matted hair, who most scholars say refer to God Siva. Then, the poet goes on to talk about others, who do not believe in this God or these four scriptures of righteousness, possibly referring to the four Vedas. This mention of others implies presence of conflicting religious beliefs, possibly Buddhism, Jainism and could be even Vaishnavism, or belief in God Vishnu, and as can be expected, proponents of this religion paint the words of those following other religions as falsehoods. Apparently, the way to thwart those disbelievers then was to conduct sacrifices and twenty one in number were done by the ancestors of this priest, informs the poet.

Next, from the past, the poet zooms on to the present when this said priest is conducting rituals in fourteen different places. He first starts with the attire of the priest, who seems to have covered himself in deerskin and this is said to be glowing atop the holy thread across the priest’s shoulders. From the priest, the poet turns to his female companions. Note how they are not one but many in number! These ladies are said to be wearing some holy ornaments and having small foreheads and long tresses. Most telling of their personality is that they speak few words. No doubt the poet says this with the approval of the patriarchal belief system he stands upon! These women are helping out in the great rituals done, where this priest seems to be pouring copious amounts of ghee, putting water to shame. The poet delights in having witnessed such a feast and says as he travels to his village in the Western mountains, from where River Kaveri flows, he will sing of this priest’s praises and blesses him to stand tall forever like the bamboo-filled, soaring Himalayas!

The highlight of this verse is the glorification of one religious belief over all the others. While this is a common theme in the myths and religious fables of most other ancient texts, it’s interesting to note that such songs are a rarity in Sangam Literature. It also gives an insight about the ways in which the Vedic religion was feverishly spread across this land in the form of sacrifices and feasts, to win over the minds of the Tamil kings and their subjects. Tussles over superiority of one religion over the other continues two thousand years later but hopefully, some day it will be understood that while the wrapper of each religion may be different, at the core, each one is but an invention to evoke human cooperation!

Share your thoughts...